What is lichen sclerosus?

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin condition which can affect any part of the skin, but in females it most often affects the genital skin (vulva) and the skin around the anus. It can start in childhood – or adulthood and affect girls or women of any age.

What causes lichen sclerosus?

The cause of lichen sclerosus is not fully understood. It is felt to be a type of autoimmune condition in which the person’s immune system reacts against the skin. Sometimes it is associated with other diseases in which the body’s immune system attacks normal tissues such as the thyroid gland (causing an overactive – or underactive thyroid gland) or the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas (causing diabetes).

Lichen sclerosus is not due to an infection – the disease is not contagious, so sexual partners cannot pick it up.

Friction or damage to the skin trigger lichen sclerosus and make it worse. This is called a ‘Koebner response’. Irritation from urine leakage, or wearing incontinence pads or panty liners can make the problem worse.

Is lichen sclerosus hereditary?

Rarely, lichen sclerosus can occur in relatives.

What are the symptoms of lichen sclerosus?

Many patients have none, but the most common symptom of lichen sclerosus is itching. As a rule the patches on the general skin surface seldom itch much, but those in the genital area do, and can also be sore if the skin breaks down or cracks. In the genital area, the scar-like process can tighten the skin, and this can interfere with urination and with sexual intercourse. Tightening of the skin around the anus can lead to problems with constipation.

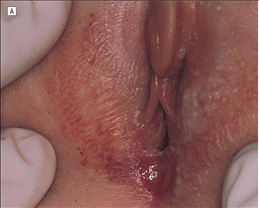

What does lichen sclerosus look like?

In females the most common site of involvement is the vulva skin. The skin has a white shiny appearance which can sometimes become raised and thickened. When there is also involvement of the anus it is described as ‘a figure of eight pattern’. Skin fragility may lead to easy bruising, blisters and erosions. There is a small risk (less than 5%) of developing a skin cancer in affected areas in the vulva. These can look like lumps, ulcers or crusted areas.

In areas away from the genital skin, lichen sclerosus looks like small ivory-coloured slightly raised areas, which can join up to form white patches. After a while the surface of the spots can look like white wrinkled tissue paper. The most common sites are the bends of the wrists, the upper trunk, around the breasts, the neck and armpits.